Above: I walk by this house all the time. I’d love to go inside

Buildings call to you. The shape of windows, the colour of a door, the height of the roof, the patterns in timber, a romantic garden: bricked-bodies reaching out for your love. Then there are those buildings which make you grit teeth, tease the blood from your heart, this guttural sixth sense of knowing that unspeakable things have occurred behind that façade. These buildings are monuments to some of our darkest fears. Most towns have them: the witch house, the murder house, the creepy building, the haunted house, the place everyone crosses the road to avoid. Gaston Bachelard sees houses as ‘a body of images that give[s] mankind proof or illusions of stability.’

Perhaps it’s these images of unstable illusions that have always attracted me to buildings and houses, not because I am an architectural enthusiast (I know almost nothing substantial about architecture) but rather the stories that are hidden inside, the memories that exist under the floorboards. I am attracted to the feelings of a space.

Outside the realm of writer dreamscapes, houses and buildings which are associated with murders, suicides, meth labs, cruelty and hauntings are called ‘stigmatised homes’. Properties ‘with history’ will often see a 25% reduction in value and take longer to sell. For some investors, this might be music to their ears: historically expensive homes going for cheap. As recent as 2016, the Amityville horror house, Jeffrey Dahmer’s childhood home, and the Kreischer mansion were all up for resale. Needless to say these are not my idea of smart, first-homeowner investments.

Buildings call to you, want to whisper their secrets in your ear. Here are four stigmatised homes, buildings and places which have stories to tell:

The Queen Mary, docked permanently at Long Beach Harbor, California

Said to be one of the most haunted ships in the world, over the course of it’s life the Queen Mary has been a luxury cruiseliner, a warship named The Grey Ghost during WW2 which carried 800,000 sailors and prisoners of war, before being restored once more as a passenger vessel.

Behind its opulent interior is a history of death, beginning in 1936 when the first captain, Edgar Britten, died from a stroke in his cabin. As the years progressed, senior second officer, William Stark, was poisoned to death after he drank from a gin bottle filled with laundry detergent (there are claims it was actually acid); a woman and a child drowned in separate incidents in the ships’ swimming pools; during WW2 three Australian soldiers threw one of the ship’s cooks into the oven, burning him alive; and in unrelated incidents two men were crushed to death by door 13 in the ship’s underbelly.

However the events of 2 October 1942 provides The Queen Mary with it’s most significant record of death. The HMS Curacao was escorting The Grey Ghost through the ocean, zigzagging through tides in an effort to confuse any U-boats that may have been hiding in the water. This routine passage for both ships became a nightmare when The Queen Mary unexpectedly caught up to the Curacoa. Colliding with the much smaller ship, The Grey Ghost split the Curacoa in half, killing many of those on board instantly. Horrifically dozens upon dozens of men were then dragged underneath the water into The Queen Mary’s propeller, their screams loud and wild, siren calls. Somehow a few hundred men, now scattered in the freezing water, managed to hold onto their lives however due to war protocol, the Queen Mary couldn’t stop to pick them up. An SOS was sent to ‘nearby’ British ships to rescue those stranded but by the time those ships arrived two hours later, only 99 men were found alive.

Hinterkaifeck Ranch/ The Gruber family farm, Germany

Before the six inhabitants of the Gruber family farm were slaughtered, rural-strong father, Andreas Gruber, reported strange and mysterious occurrences to neighbours and friends: there had been odd footprints in the snow leading from the forrest to the house but none leading back. He told them how their last maid had left six months before because she believed the house was haunted, kept hearing unsettling knocks throughout the house, kept hearing someone walk around in the darkness. Mystery after mystery .

The day Maria Baumgartner, the new Gruber family maid moved in, a final mystery came for them all, mattock in hand.

Exact events surrounding the day of the unsolved 1922 murders remain unknown however the best anyone has ever been able to determine is the following: one by one, Andreas Gruber (63), Cazilia Gruber (72), their widowed daughter, Viktoria Gabriel (36) and her daughter, Cazilia (7) found their way to the barn and were murdered by someone wielding a mattock. Shortly thereafter the perpetrator walked into the house, into a bedroom where 2 year old Josef was still a ball of sleep in his cot and killed him before heading to the bedroom of Maria Baumgartner (44) and killing her too. Over the course of a few days, the killer made themselves at home, eating food from the kitchen, feeding the farm animals and making a fire to keep warm. When days then nights on the farm became too silent, the murderer left as quietly as they had arrived, leaving behind the family’s remains for neighbours to discover four days after the crime.

Although the house was demolished in 1923 and a shrine erected in its place, the farmlands still grow green, still waits for the murderer to be found.

Pripyat Amusement Park, Pripyat, Ukraine

The children of Pripyat daydreamed about the new amusement park for months leading up to its scheduled grand opening of 1 May 1986: how fast would the carousel go? How hard could they drive the dodgem cars into each other? What would be seen from the Summer-yellow coloured Ferris Wheel? How many sweets could they eat before feeling sick?

As children counted down the days, the town of 50,000 residents (and founded in 1970) went about their lives: workers made their way down the road to the Chernobyl NPP like they always did, mothers dropped off their children at daycare before going to work, teenagers made weekend plans. Everyone watched the construction of the amusement park move from skeletal mechanics to full grown life. And they waited.

History tells us what happens next. After the devastating Chernobyl disaster on 26 April 1986, Pripyat, like so many other towns nearby, was evacuated a few days later. There are conflicting reports as to whether the amusement park ever opened with some claiming it did for a few hours on the 27 April and others stating it never opened at all.

Pripyat has been a ghost town for over 30 years. Residents ever returned. The amusement park remains: instead of children’s feet hammering laughter into asphalt, neon green moss spreads like a cancer, fights with the decimated shades of green, brown and bleached grass growing through concrete faultlines. The Ferris wheel, sour-yellow rust, is an angry God, looms over strewn Dodgem cars and the carousel. The buildings in Pripyat are old bodies dropping paint, dropping walls, dropping skin, fingernails, hair. It’s a town largely without colour, without sound, without life. Some days not even wind comes to play at the amusement park.

Pripyat is now a destination for ‘extreme tourists’ armed with Geiger counters and a curiosity for what might have been.

The John Sowden House, Los Feliz, United States

Before this Los Feliz house was built in 1926, painter and photographer John Sowden asked his friend, Lloyd Wright, to design a home for him, something architecturally significant where he could entertain his Hollywood friends. The result was a Mayan revival house with a cave-like entrance and tomb-thin staircases. Although ridiculed by many for it’s appearance this would be a home to make memories in.

Years passed. John sold the house in 1930 and after many owners it was eventually bought by Dr George Hodel and his family in 1945. At first the Hodel children embraced the labyrinthine house, fell in love with the magic of a building that was a world onto itself. But not all was golden. George frequently beat his sons in the basement, was accused of raping his daughter.

The Hodel’s eventually sold the house and when George died in 1999 his son, Steve, then a retired LA homicide detective, found two photos of a dark haired woman amongst his father’s belongings. She looked familiar. Memories of overheard conversations from Steve’s childhood in that house came back.

15 January 1947: over eleven miles away from Los Feliz, Betty Bersinger and her three year old daughter were out for their morning walk throughout Leimert Park. Fresh air, car movement, birdsong. Joy. It was then the three year old noticed the mannequin in the grass beyond the sidewalk. What an odd place to leave one. Betty went to the mannequin to investigate. Closer, closer she went, her body probably registering what lay in the grass before she had the chance to verbalise horror: the body of Elizabeth Short, cut in half, drained of all blood. Somebody had slashed Elizabeth’s mouth from the corners to her ears, had sliced whole pieces of flesh from her thighs and breasts. In that moment: horror of what men thought they could do to you and your body, your life. Betty would carry this with her for the rest of her days. Betty screamed, called the police. In the moments after the murder, reporters rushed to uncover as much ‘sordid’ information about the victim by any means necessary. They even gave Elizabeth a new name, ‘The Black Dahlia’, these attempts at reducing her to an image, someone not real. At one stage, the LA Examiner located Elizabeth’s mother, Phoebe, told her that Elizabeth had won a beauty contest and would she mind sharing stories about her daughter’s personal life? Phoebe agreed, opened up. It was only after they nabbed their information that the Examiner told Phoebe that her daughter had been murdered.

The murder remains unsolved to this day. Except for one thing: Steve Hodel’s memories. After finding the photos he asked older family members to fill in memory-gaps for him, answer the questions he’s always had about his sadistic father. After long conversations, Steve believed Elizabeth had been to his childhood house in Los Feliz. He believes that his father tortured, murdered and dissected her body in the basement.

Sometime after 2011, Steve Lopez, a reporter for the LA Times went through a stack of old DA files on George Hodel. At the time Hodel was being investigated for his daughter’s rape, the house was bugged and everything was recorded. Steve Lopez found those tapes, found those transcripts in the file. He listened, he read and discovered: George had in fact been a suspect in Elizabeth’s murder. There was also another tape in the file, one where George can be heard on the phone to a friend saying, ‘‘Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia… they couldn’t prove it now.’

Somewhere in that house is a memory with an answer.

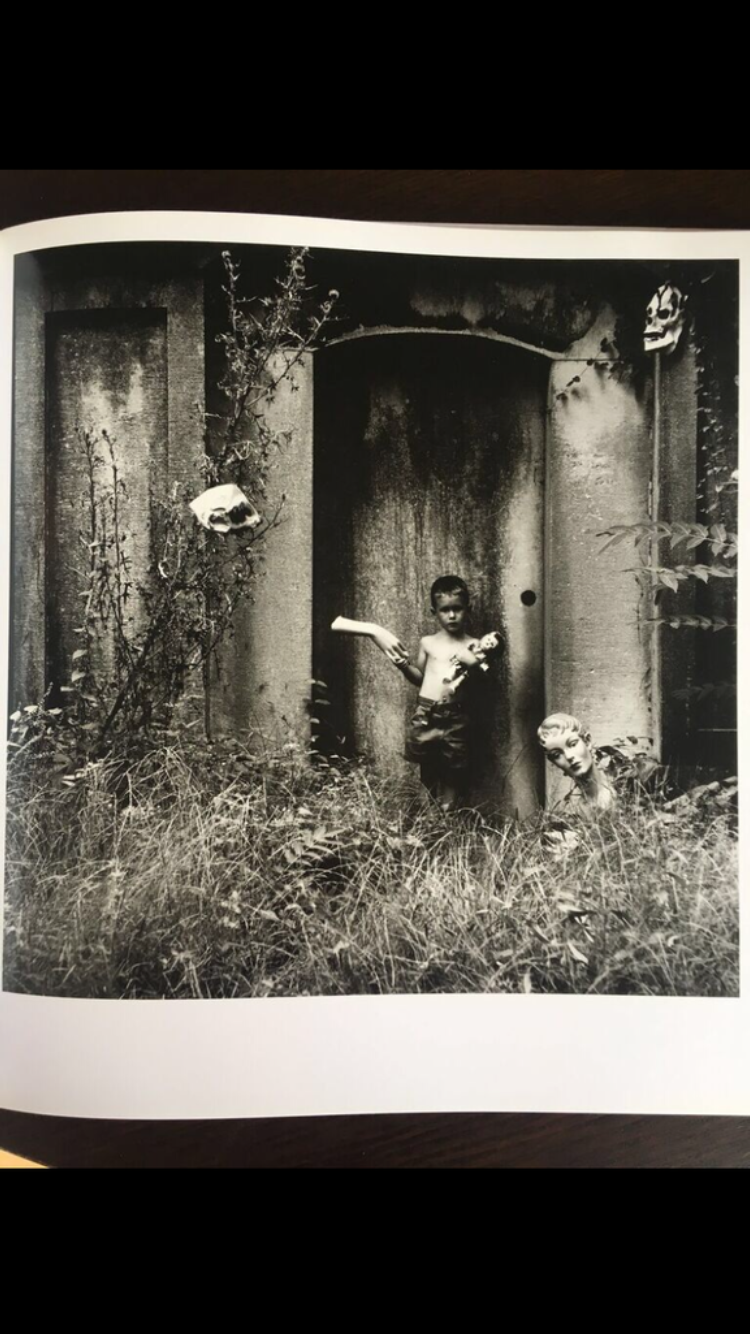

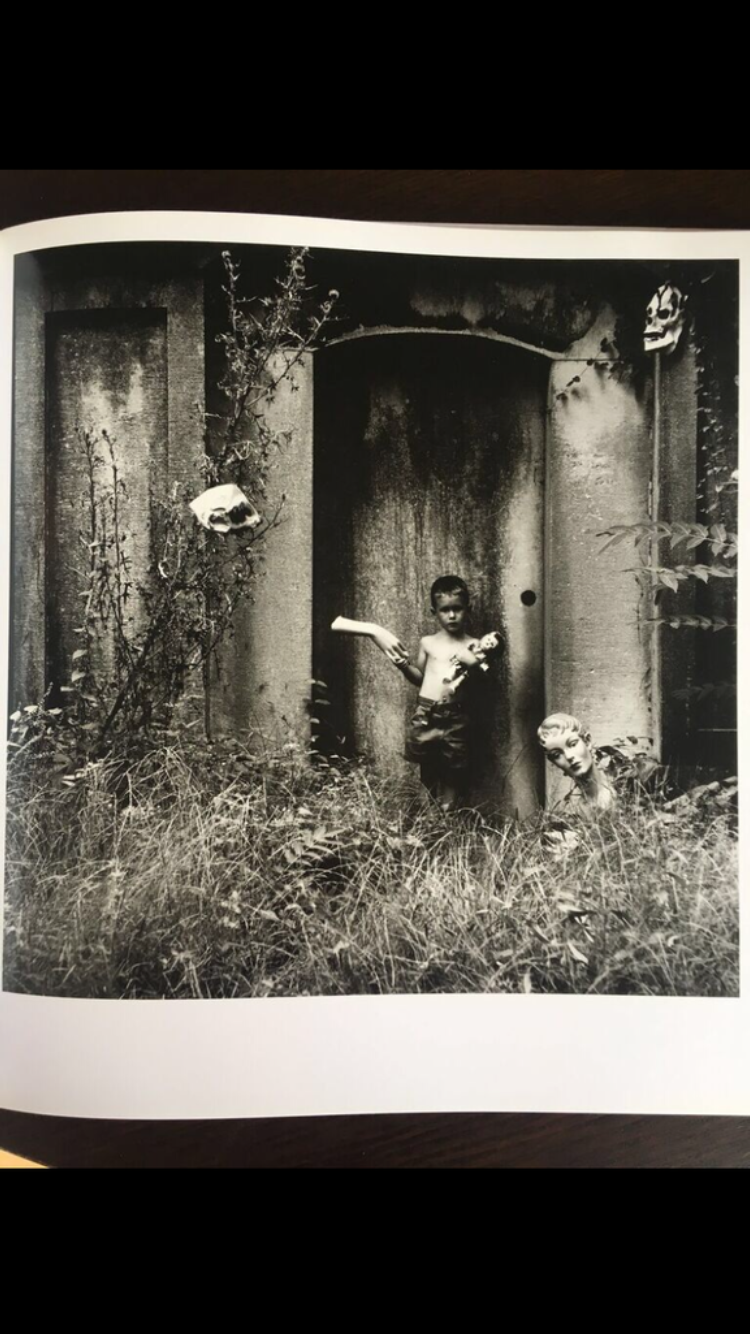

Above: Ralph Eugene Meatyard. One of my favourite photographers. For obvious reasons